A new study has found that men recovering from alcohol use problems tend to have less brain tissue in areas linked to thinking and emotion compared to healthy men. The research also found that these brain differences were related to difficulties with memory and mood, suggesting that changes in brain structure may influence how severe a person’s alcohol problems become. The findings have been published in Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging.

Alcohol use disorder is a widespread health problem that affects millions of people around the world and is known to be influenced by a mix of genetic, developmental, and environmental factors. Previous studies have suggested that heavy alcohol consumption not only affects behavior but also brings about changes in the brain, especially in regions that control thinking, memory, and emotions.

Isabel Cristina Céspedes, the senior author of the study and associate professor at the Federal University of São Paulo, was motivated to examine this because of “the suffering of individuals with alcohol use disorder and their families with low success rates in treating this chronic disease, which is destructive from a biological and psychosocial point of view.”

Céspedes and her colleagues specifically wanted to explore whether the differences in brain volume seen in patients with alcohol use disorder were linked to difficulties in cognition and mood, and whether these brain changes might help explain why some people develop more severe alcohol-related problems. By examining these relationships, the researchers hoped to gain a clearer picture of the biological and behavioral pathways that contribute to the disorder.

To conduct their research, the investigators recruited two groups of male participants. The first group included 50 individuals who had been recently detoxified from alcohol and were receiving treatment for alcohol use disorder at a treatment center in São Paulo, Brazil. The participants in this group had been abstinent for between 10 and 15 days and had been given a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder by a psychiatrist. The second group consisted of 50 individuals who did not have alcohol dependence and were classified as having low risk for substance use. These participants were recruited from a hospital associated with a local university.

All participants underwent high-resolution scans of their brains using magnetic resonance imaging on a 3-Tesla machine, which allowed the researchers to measure the volume of various brain regions in great detail. The imaging process produced three-dimensional pictures of the brain that the team analyzed with a technique that identifies and measures the amount of gray matter in different regions. Gray matter is important because it contains the nerve cells that help process information, control emotions, and guide behavior.

In addition to the brain scans, participants completed several tests designed to measure their cognitive abilities and emotional states. Furthermore, the participants filled out self-report questionnaires that measured levels of anxiety and depression, two common mood issues that are often seen in people with alcohol use disorder. The researchers also gathered detailed information about the participants’ substance use habits, their educational background, and other clinical details, such as family history of alcohol use disorder and previous treatments.

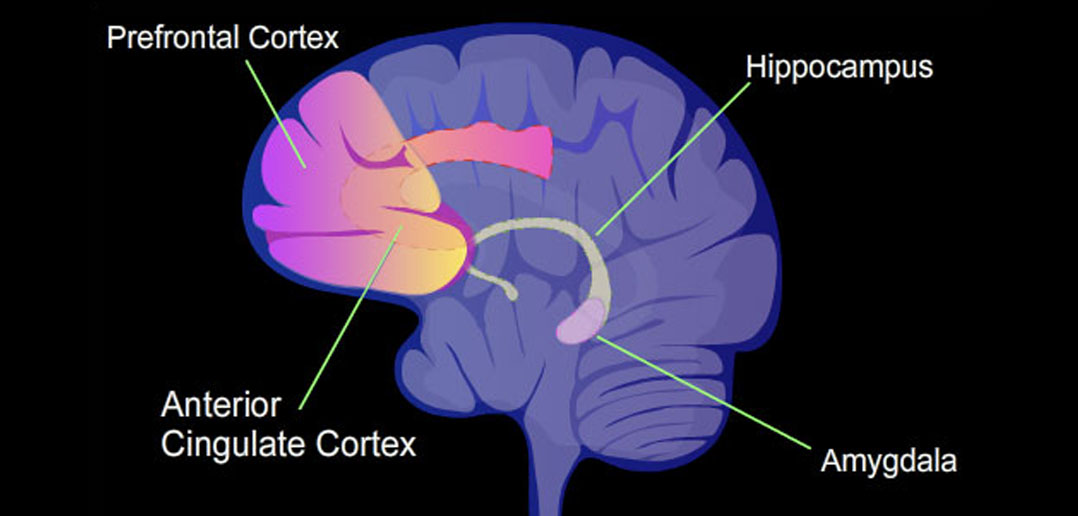

The researchers found that the group with alcohol use disorder had noticeably lower amounts of gray matter in several brain regions compared to the group without the disorder. The reductions were particularly evident in parts of the frontal lobe, which is known to be involved in planning, self-control, and evaluating choices, and in regions of the limbic system, which helps regulate emotions and long-term memory.

For instance, areas such as the orbitofrontal cortex and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex showed lower volumes in patients with alcohol use disorder. These areas are important for making decisions based on reward and punishment and for regulating emotional responses. In addition, other areas related to emotional processing, such as the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex and parts of the hippocampus, also showed reduced gray matter.

In parallel with these brain differences, the individuals with alcohol use disorder performed more poorly on memory tests. They had difficulties recalling information both immediately after learning and after a delay, and they also struggled with recognizing previously presented words. Although differences in decision-making performance between the two groups were less pronounced, the overall pattern suggested that reduced brain volume in specific regions was associated with worse cognitive performance and higher levels of anxiety and depression.

The data indicated that the areas of the brain involved in emotional regulation appeared to affect the severity of alcohol-related problems indirectly by influencing mood. In other words, lower brain volume in these regions was linked to more pronounced symptoms of anxiety and depression, which in turn were related to more severe alcohol use problems. This suggests that the emotional difficulties experienced by people with alcohol use disorder may be partly rooted in structural changes in the brain.

“Traumas and environmental stimuli that leave scars on the neural circuits associated with emotion processing are potent vulnerability factors for the disorder,” Céspedes told PsyPost.

It is important to note that while the study found clear associations between brain structure, mood, and memory performance, the relationship between brain structure and decision-making was not as straightforward. The performance on the decision-making task did not differ significantly between the groups, which could be due to the complexity of decision-making as a process or to the limitations of the test used. However, the overall evidence points to a significant connection between brain volume in key regions, emotional disturbances, and cognitive difficulties in individuals with alcohol use disorder.

Despite these informative findings, the study has some limitations that should be considered. The research focused exclusively on male participants, which means that the results may not apply to women with alcohol use disorder. In addition, many of the individuals with alcohol use disorder also had a history of using other substances, even though alcohol was the primary drug of abuse. This makes it harder to determine whether the observed brain differences are solely due to alcohol or if they might also be influenced by other substances.

The study also did not account for genetic differences, which might influence brain development and contribute to an individual’s susceptibility to alcohol use disorder. Recognizing this gap, the researchers are preparing a genetic study that will be published soon. Looking forward, Céspedes hopes “to unite all the factors in a publication associating the genetic bases with the individual’s mental functioning, together with psychosocial factors, and to try to better understand the complexity of this disease.”

The study, “Reduced gray matter volume in limbic and cortical areas is associated with anxiety and depression in alcohol use disorder patients,” was authored by Laís da Silva Pereira-Rufino, Denise Ribeiro Gobbo, Rafael Conte, Raissa Mazzer de Sino, Natan Nascimento de Oliveira, Thiago Marques Fidalgo, João Ricardo Sato, Henrique Carrete Junior, Maria Lucia Oliveira Souza-Formigoni, Zhenhao Shi, João Ricardo N. Vissoci, Corinde E. Wiers, and Isabel Cristina Céspedes.